Hartford, Connecticut

Art and History Archive

The art and histroy archive is another Global Studies product of mine. In this product, I seek the narrative in art instead of the progression of art style. The goal of my archive is to explain and show paintings that recorded drastic social changes in certain periods of human history. I will mainly focus on two centuries: the 19th century and the 20th century. In each century I will look into three artists and focus on one or two of their works. Unlike in my research paper, the archive will be mainly composed of pictures of paintings, sketches, and sculptures, which I organized based on time, and under each work, there will be short descriptions and analysis of the piece.

19th Century

Jean-François Millet and the Laborious Working Class

Before the mid 19th century, appearing in oil paintings were always considered as a privilege only for the upper class. Although some laborers appeared in paintings, they were mainly the victims of satires or insults. At the same time, the role artists play in creating art is also changing. Painting used to be an assigned job, and painters only started working when the buyer (normally nobilities, royal families, or rich upper class) made an offer to the painter with an amount of money and a well-established idea. The ideas of the artwork were not decided by the artists, and artists hardly do any paintings for their interests. However, by the time Millet created works on the laborious workers, he was painting for himself. This also led to the emergence of impressionism.

Most of Millet’s paintings that featured the farmers were created during and after the French revolution of 1848 when the power of the upper class and nobility was severely weakened. On the other hand, the contributions of the lower class people were significantly glorified since they are the bases of the country. Millet took the description of real-life as the highest principle of creation. Artists like Millet began to face up to reality, instead of the overly-decorated life of the upper class, and boldly describing the beauty of laboring.

The Gleaners

In The Gleaners, three peasant women are gleaning under the hot sun, and their diligence created a contrast between the rich harvest scene in the countryside and the bitter work of the peasants, truly showing the hardships of the people's life and profoundly revealing the class division behind it. Peasant paintings in the 19th century produced and showed a profound class conflict and the social environment is inseparable.

Vasily Surikov and the Epic History on Canvas

The Morning of Strelets' Execution

Surikov is a genius in painting historical events. As long as the scene is emotional and epic enough, he can always capture the moment perfectly. Morning of Strelets’ Execution was his college graduation work. The scene of this painting took place in the late 17th century during the Russian cultural reformation under the lead of Peter the Great. The revolution that replaced some of the traditionalist and medieval social and political structures with ones that were modern and scientific, and the Morning of the Strelets’ Execution depicts a coup in this revolution. One of Peter the Great’s relatives, Sophia secretly conspired with armies to rebel against the revolution. However, the plan was brought to light, and Sophia was imprisoned into a castle. All of the army members that participated in the rebellion were also put to death. Among all of the figures in the painting, one soldier who had a candle in his hand stared directly into the eyes of Peter I who was on a horse and staring back. Surikov accurately captured the emotion on the two’s faces, emphasizing the conflict between the supporters of the old system and the new system.

Boyarynya Morozova

Boyarynya Morozova was about the religious reform in Russia, which is an earlier story than the cultural revolution in Morning of the Strelets’ Execution. During the reign of Alexei Mihajlovic from 1653 to 1656, patriarch Nikon of Moscow imitates the Greek church system and carrying out a series of reforms: revision of the bible and other church books, unification of church rites, and the priesthood over the secular state. The reformation led to conflicts between the believers of the traditional church system and the believers of the reformed church system. Morozova is the woman chained on the sleigh, and she is the former one. Her index and middle pointed directly into the sky, which is the symbol of the cross used before the reform. A man in the crowd, bared feet with chains all over his body, also pointed two fingers to the sky as a form of response to her rebellion.

Every country has its own painful memories, but the ways different countries express it are different. Under Surikov’s paint brush, even the people on the edge of death radianced their unbending will.

Ilya Repin: the Master of Depicting Emotions

There is a saying in China that “two tigers cannot live in the same mountain”. This is true in many situations, but not in art. Along with Vasily Surikov, another Russian historical painter during the same time, Ilya Repin, also spent his entire life painting histories on canvas but different from Surikov. If there ever is another Russian artist whose importance is comparable to Surikov, it would be Repin. If we look closely into Repin’s and Surikov’s paintings at the same time, the clumsiness in Surikov’s brushstroke is immediately revealed. The emotions featured in Repin’s work are far more vivid and accurate than that of Surikov. But we can’t compare the two as for who is better. It is like comparing pork belly to steak; neither one is better than the other, and the only thing the audience should do is to enjoy each of their brilliance.

Among all of the Russian paintings in the 19th century, Repin’s artworks were almost the only ones that influenced outside of Russia. Countless Western painters who lived in the same period with Repin, with skills not nearly as good as his, were written into world art history, while Repin and Surikov are being washed away in the river of history. They are the victims of cultural hegemony, so are thousands of artists in the history of art, and that is disappointing even just to think about.

Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on November 16, 1581.

Ivan the Terrible (1533-1584) was the first tsar in Russia’s history. He ascended the throne at the age of three. When he was 17, Ivan murdered the regent and began to rule the kingdom on his own. He was known in history as "Ivan the Terrible" for his violent, suspicious nature and his brutal methods to suppress uprisings and aristocratic opposition against him. On November 16, 1581, Ivan made an irreparable mistake when, under the heat of rage, he killed his eldest son, who tried to challenge his authority, with his cane. In the painting, Ivan held his dying son in his old, skinny arm; his left hand tried to stop the bleeding wound as an attempt to save his son’s life. The eyes of Ivan were filled with horror and sorrow: horrified that he had just murdered the heir of the throne; sorrowful that he killed his beloved son. Repin's meticulous depiction of Ivan’s complex emotional changes couldn’t be more perfect, and it fully reveals the tragedy behind the life of this tyrant.

The reason paintings like Ivan the Terrible and His Son Ivan on November 16, 1581, are underrated is due to its narrative. Western art history tends to praise art that only focuses on art itself. Historical paintings include too many elements besides art, so it couldn’t be considered as a pure form of art.

20th Century

Kaethe Kollwitz and the Peasants in War

Käthe Kollwitz was born in Konigsberg on July 8th, 1867. Among all of the female artists throughout the entire western art history, only a few were able to be considered to have the same weight as Kaethe Kollwitz’s. Her depiction of life and death, happiness and sorrow, war and peace, and especially moments that shine the love of motherhood, is extremely vivid and contains a tremendous amount of power.

In the year WWI began, Kollwitz’s eldest son, Peter Kollwitz, was killed on the battlefield of Flandern. The death of Peter hit Kollwitz hard, and she didn’t produce a single artwork in the next five years until 1919 after she became the first female ever elected to be a member of the Prussian Academy of Arts. In 1933, Hitler imposed suppression on the publication of artworks. Kollwitz’s prints were banned from publications and exhibitions, and all of her. She was relieved of all duties and her work was banned from exhibition and publication and was dismissed from all of her duties. But by this time, the spirit of Kollwitz’s work had won respect all over the globe, and the reality in her prints will forever be remembered.

Woman with Dead Child

Woman With Dead Child is a good example of a non-narrative art. The etching does show a woman holding a child in her arm, but it is different from being narrative. Narrative art depicts a specific event or person in history, such as Ivan the Terrible by Repin. However, Kollwitz’s etching didn’t feature any specific event or person. The woman and child figure were abstract ideas that miniaturized the brutality of the war. Like any other painting, Woman with Dead Child has a story behind it, but it was told through the features rather than the historical events behind it.

Woman with Dead Child is an example of Kollwitz’s work that particularly demonstrates the heaviness of maternal bond and the grief of death. The woman in the picture embraced her child tight in her arms, hoping that he can open his eyes for one more time. The emotion created by the figures is powerful, and the black and white color further strengthened the sorrows. She pitied the peasants, and Woman with Dead Child is one of many of her works that portrayed the tragic fate of the working class.

The two figures in the etching were modeled by Kollwitz herself and her seven-year-old son Peter, and she would have never thought that the scene would one day turn into reality. After all, even the artist herself is just another victim of war and class division.

Although Xu Beihong has hardly any reputation in Western Art History, he is respected as the founder of Chinese modern art education and the pioneer of introducing Western art. Before Xu, Chinese art education was almost disconnected from the entire world, and the progressive western art forms were not paid with any attention. Art academies do not teach oil paintings or sketches, nor were human anatomies involved in the curriculum, and the primary art form in art academies were ink washing paintings, a traditional style that can be traced back thousands of years.

Xu was the man that changed the system of art education in China. At the age of 24, he traveled abroad and studied in the National School of fine arts in Paris to learn oil painting and sketch. When Xu was 32, he returned to China and began to advocate incorporating western painting techniques: the focus on light, shape, the accuracy of anatomy, and the connotation, into the traditional Chinese paintings. His dedication helped China to open to modern art around the world. So far in the 21st century, China has only embraced world art for 100 years. Compared to European countries such as France and Italy, which has been the pioneer in art development for more than 400 years, art in China is still like an infant who is learning to speak.

Xu Beihong: The Leader of Chinese Oil Painting

Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers

The story of Tian Heng and His 500 Followers sourced from the Biography of Tian Dan in the Record of the Grand Historian records. Tian Heng was the name of an old royal family of the Qi kingdom in the 200 BC. It was towards the end of the Qin Dynasty when war and conflicts arose. Tian Heng and his 500 followers lost in a battle against Liu Bang and were forced to escape to an island. Liu Bang then threatened Tian Heng to obey his rule otherwise he would lead an army and kill Tian Heng and all of his followers. However, Tian Heng and his followers didn’t submit to Liu Bang’s tyranny, and all of them committed suicide. The decision made by Tian Heng and his people shows the "mighty and unyielding" will of the people.

Xu Beihong used the story behind this story to reflect another historical revolution in China during his life. In 1927, Kuomintang led by Chiang Kai-Shek began to spread its influence in China. Countless intellectuals abandoned the Communist Party of China and joined the Kuomintang. In Xu’s perspective, this is a form of betrayal, so he painted this piece to rearouse the “mighty and unyielding” will of the Chinese, and not to betray their party. The painting is created through the eyes of Xu. We cannot judge whether it is correct or incorrect, and let us just treat it as a scene that depicts a memory of China: a time when a country didn’t have a leader, and citizens were suffering in the chaos created by parties.

Jiang Zhaohe and the Suffering People

July 7th, 1937, was the beginning of a nightmare for China. During the night of the day, the Japanese army attacked the Wanping City in Beijing, marking the start of the Second Sino-Japanese War. The war lasted eight years long and ended on August 15, 1945, when Japan unconditionally surrendered to the Allies. On the same day, a Chinese artist created a painting of a young girl kneeling on the ground with her eyes looking at the sky. The title of this painting is Father Will Never Come Back Again, and the artist is Jiang Zhaohe.

Father Will Never Come Back Again

The title of this painting already told the story behind: the young girl’s parents sacrificed in the war. After the Sino-Japanese war ended, countless paintings portrayed the greatness of victory. But why did Mister Jiang choose to paint a girl who suffers in despair on a day when the whole country joined in jubilation? No matter if it was a victory or defeat, the truth of war is that thousands of families were broken apart and countless people lost their loved one.

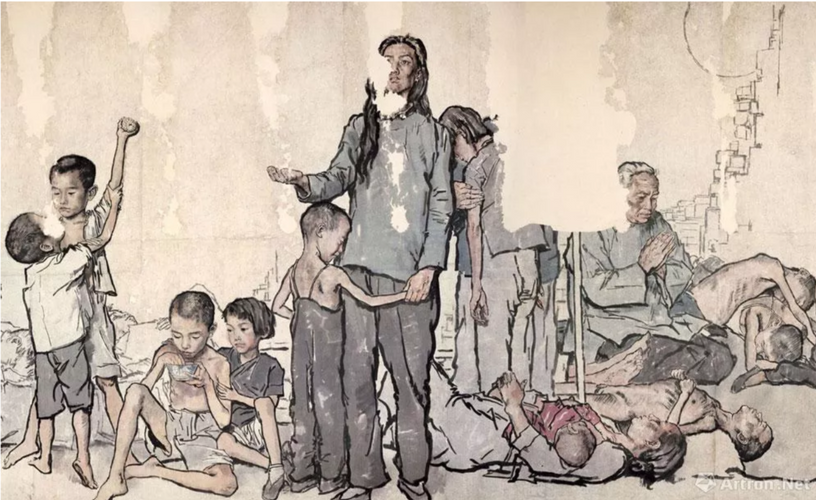

Refugees

In Jiang Zhaohe’s entire life, the most important painting by him was the Refugees created during WWII. The painting features more than one hundred diverse citizens in war. No two people shared the same expression or gesture. Jiang not only captured this moment in these refugees' lives, but he also captured the cruelty and despair of war. Throughout history, there are hardly any paintings that portray scenes of happiness. And even if there are, the audiences will hardly feel the happiness in the painting. But when looking at pieces that depict tragedy, it is the complete opposite, and the audience can be truly affected by the emotions.

Refugees were painted in 1943, and soon after that, the painting was exhibited in the Tai temple of Beijing. But the exhibition only lasted one day before the gendarme banned the event. The painting was re-exhibited in Shanghai for two weeks. But the event faced a similar ending: the Japanese authorities banned the exhibition and confiscated the painting. When everyone thought the painting was forever lost, it miraculously reappeared in a warehouse with half of it gone and sections molded. The original paintings were longer than 30 meters, but only 14 meters were eligible by the time it was found.

The paintings were transferred back to Jiang Zhaohe’s hand, but under shame and dishonor instead of glory. During the war, Jiang was reported to have a connection with a traitor of the country, causing him to be labeled as an anti-communist. The hero, who compassionate and pitied the innocent people, became the enemy of the people. He turned into a refugee, exiled by the country he dedicated everything into.

The biggest disaster of this painting has yet to come. In the Cultural Revolution (1966-1976), Refugees was labeled to be an“anti-communistic poison” and was confiscated and almost destroyed. Years after the Cultural Revolution, the painting was lucky enough to be found again, and the humiliation of this painting finally came to an end. In 1979, under the authentication of The Central Academy of Fine Art, Refugees was re-identified to be “a work of patriotic realism”. It took more than 30 years for it to be recognized and appreciated. Refugees not only portrayed the realistic side of WWII, but it also recorded the progression and development of entire China.

Sources & Citation

Danqing, Chen. Parts, Episode 13, 08 September 2015

Danqing, Chen. Parts, Episode 3, 30 June 2015

“The Revolutions of 1848.” School History, schoolhistory.co.uk/notes/the-revolutions-of-1848/.

“Millet Paintings, Bio, Ideas.” The Art Story, www.theartstory.org/artist/millet-jean-francois/.

“Ilya Repin - 541 Artworks - Painting.” Www.wikiart.org, www.wikiart.org/en/ilya-repin.

“Jean-Francois Millet - 129 Artworks - Painting.” Www.wikiart.org, www.wikiart.org/en/jean-francois-millet.

Manaev, Georgy. “Most Famous Russian Paintings Explained: 'Ivan the Terrible and His Son'.” Russia Beyond, 5 May 2019, www.rbth.com/arts/330317-ivan-terrible-and-his-son-painting.

David. “Boyarina Morozova.” ICONS AND THEIR INTERPRETATION, 12 Aug. 2017, russianicons.wordpress.com/tag/boyarina-morozova/.

“Käthe Kollwitz: MoMA.” The Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/artists/3201.

Kollwitz, Käthe. “Käthe Kollwitz. Woman with Dead Child (Frau Mit Totem Kind). 1903: MoMA.” The Museum of Modern Art, www.moma.org/collection/works/273959

“Kathe Kollwitz - 46 Artworks - Painting.” Www.wikiart.org, www.wikiart.org/en/kathe-kollwitz.

“Refugees.” NAMOC, www.namoc.org/en/collections/201306/t20130619_253960.htm.

“Xu Beihong - 97 Artworks - Painting.” Www.wikiart.org, www.wikiart.org/en/xu-beihong.

“Jiang Zhaohe.” Artnet, www.artnet.com/artists/jiang-zhaohe/.

“The Story of Tian Heng and His Five Hundred Followers - Google Arts & Culture.” Google, Google, artsandculture.google.com/story/the-story-of-tian-heng-and-his-five-hundred-followers/hgLyXy269TwKKQ.